Webcams track eye and head movements, microphones record room noise, and algorithms record how often the subject moves the mouse.

Eric Johnson, a privacy-conscious computer science student preparing for his freshman year at the University of Miami, was concerned this fall when he learned that two of his professors would require him to use Proctorio digital proctoring software for their classes, according to Motherboard.

The software turns students’ computers into powerful observers: webcams track eye and head movements, microphones record room noise, and algorithms record how often the subject moves the mouse, scrolls up and down the page, and presses keys. The program flags any behavior that the algorithm deems suspicious for later review by the class instructor.

In the end, Johnson never had to use Proctorio. Shortly after he began tweeting about his concerns and posting a simple code analysis of the software on Pastebin, he discovered that his IP address had been banned from the company’s services. He also received a direct message from Proctorio CEO Mike Olsen, who demanded that he delete posts on Pastebin. Johnson refused to do so and is now waiting to see if Proctorio will take more specific legal action, as it has done with other critics in recent weeks.

His case is just one example of how students are rebelling against the use of digital proctoring software and the aggressive tactics used by companies in response to these efforts.

In recent weeks, students have launched online petitions calling on universities around the world to ditch the tools, and faculty at some campuses, such as UC Santa Barbara, have launched similar campaigns, arguing that universities should explore new forms of assessment rather than observation. students.

“We need to really think long and hard about how we adapt," Jennifer Holt, professor of film and media at UCSB, told Motherboard. "We have to protect our students."

Video surveillance at home

Algorithmic control software has been around for several years, but its use has skyrocketed as the COVID-19 pandemic has forced schools to move quickly to distance learning. Proctoring companies cite studies that 50 to 70 percent of college students will attempt to cheat the system in some way, and warn that cheating will run rampant if students are left unsupervised in their own homes.

Like many other technology companies, they also object to the suggestion that they are responsible for the use of their software. While their algorithms detect behavior deemed suspicious by the application’s developers, these companies claim that the final decision whether cheating has taken place is in the hands of the class instructor.

“Any plan that calls for schools to simply stop using proctoring will make cheating more common than it already is, posing a serious threat to all higher education,” Scott McFarland, CEO of ProctorU, another proctoring service provider, wrote to Motherboard.

Comparing the deterrent effect of his product to that of more widespread video surveillance technology, he added: "We may not like the idea of being watched every time we visit a bank or store, but no one suggests filming them."

There is little peer-reviewed evidence on how digital control affects student honesty and test-taking ability, and the small study on the subject does not provide a clear consensus.

A 2018 study of 2,686 students across 29 courses found that those whose exams were not tracked by Proctorio scored 2.2 percent lower than those whose exams were. The authors concluded that the results were likely the result of deception by students not using Proctorio.

But a 2019 study of 631 students found that test subjects who experienced higher levels of anxiety during exams performed worse, and that students tracked by monitoring software experienced more anxiety than those who did not take exams. .

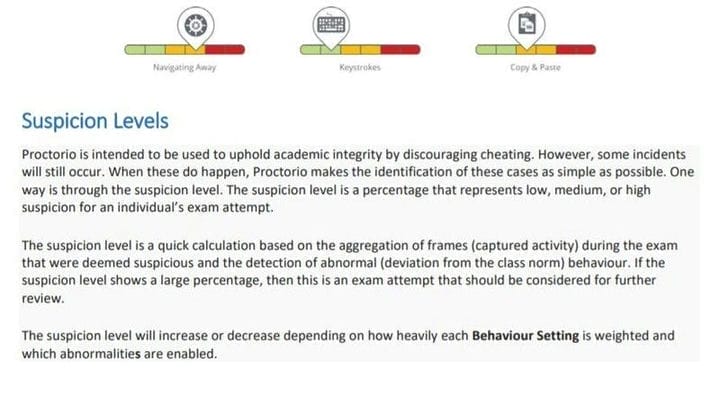

A slide from Proctorio’s reference material detailing how the system measures "levels of suspicion" during student taking exams.

In background documents that Proctorio provides to universities, the company explains that its software detects whether a test taker ‘s "suspiciousness level" at any given moment is low, medium, or high by detecting "abnormalities" in their behavior.

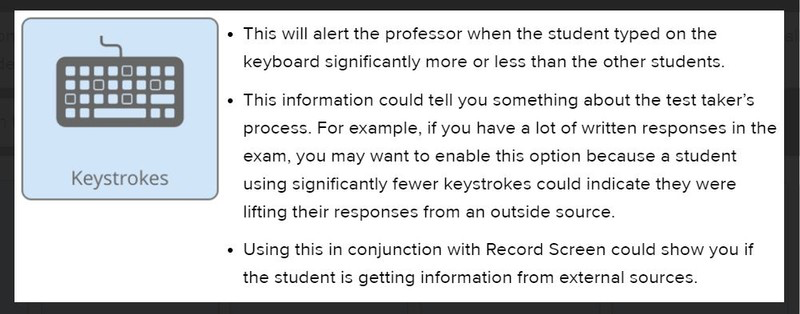

If a student looks away from the screen more than their peers taking the same exam, they are flagged as abnormal. If they look away less frequently, they are labeled as abnormal. The same goes for how many keystrokes a student does when asked how many times they press, and a host of other metrics. Deviation from the standard deviation results in a flag.

This methodology is likely to result in an unequal study of people with physical and cognitive impairments or conditions such as anxiety, Shea Swauger, a research librarian at the University of Colorado Denver’s Auraria Library who studies educational technology, told Motherboard.

“These encoders mathematically define the ideal student body: how often it does or does not fulfill these certain attributes, and anything outside of that ideal is considered suspicious,” he said.

A slide from Proctorio’s reference material detailing how the software detects "outliers" by analyzing keystroke combinations.

Proctorio strongly disagrees with this assessment. "Most importantly, we’re not making any academic decisions, we’re just providing a faster way for [teachers] to test students on an exam based on what they’re looking for," said Olsen, CEO of Proctorio. “Teachers can choose which types of behavior to track and decide if deviance is cheating,” he added.

Students from several U.S. schools told Motherboard that while teachers ultimately decide whether and how to use exam monitoring software like Proctorio, they often do so without direction or restriction from school officials.

“To the best of my knowledge, every academic department has almost complete agency to design their curriculum, and each professor is free to design exams and use whatever monitoring he sees fit,” Rohan Singh, a computer engineering student at Michigan State University, said Motherboard.

In April, a University of Colorado student tried to convince the administration to drop Proctorio by publishing an article critical of algorithmic proctoring in the journal Hybrid Pedagogy. In response, Proctorio sent a letter to the magazine demanding a retraction. The editors of the magazine refused.

The company’s response to Ian Linkletter, a learning technology specialist at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, was even more blunt. After Yang began posting instructional videos and Proctorio documents on Twitter explaining the company’s abnormality, the videos were removed from YouTube and Proctorio filed an injunction to stop Linkletter from sharing his training materials.

In March, faculty at the University of California sent a letter to the school administration stating that they were concerned that ProctorU would share student data with third parties. The faculty asked to terminate the contract with the company and dissuade professors from using similar services. In response, ProctorU’s attorney threatened to sue the faculty association for defamation and violation of the law.